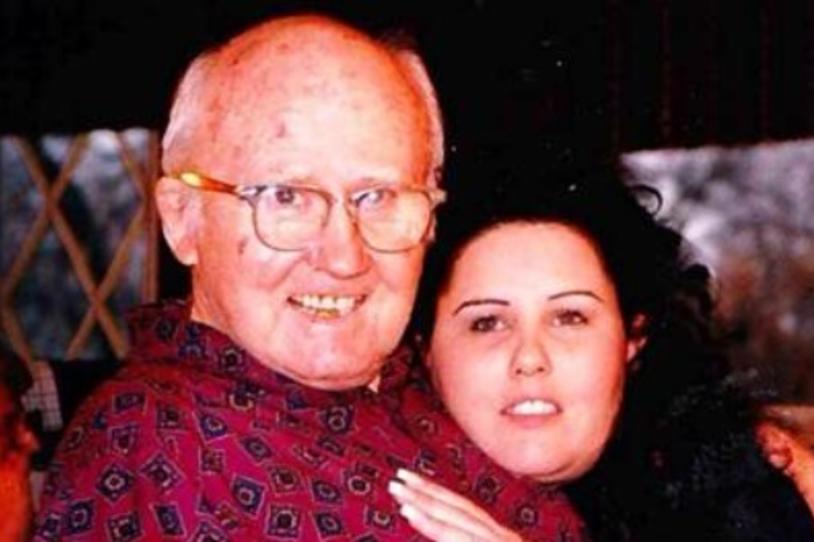

Pierce J. Butler with his daughter Julia Gorham-Wall.

When my father was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in the mid-1960s, life for my family changed quickly. One of our most immediate challenges was that he lost his job because his employer could not read his handwriting – a sudden change in handwriting is often a sign of PD.

He was in his early 30s with four children, a wife carrying his fifth (me) and a house in the suburbs of Detroit. They were living the American dream. Before PD, the biggest challenge they faced was getting us all dressed and out the door on time for Sunday mass.

My dad lived with Parkinson’s for a long time, passing away in 2001. The lessons he and my mom taught us along the way set the groundwork for me wanting to care for others. But after living through my dad’s experience, I was never looking to enter a field related to PD. I wanted to be a nurse but in any area except neurology. For many years, I worked in other specialties and then, out of nowhere, I got an offer to work at a neuroscience institute.

In my role now, I coordinate with movement disorder physicians and PD patients to increase the quality of specialized care. From treatment and education to making recommendations on quality of life issues and getting involved in research studies, I am able to provide care on many fronts including sharing my story with all of my patients. I want them to know that I understand their experience on both professional and deeply personal levels.

Growing Up with Parkinson’s

My mother, Ruth, went to work and Dad stayed home. During that time, so little was known about the disease. One physician advised Mom to have Dad institutionalized, an inconceivable notion today. In a way, I’m glad that doctor uttered those words because he lit a fire in her that continues to glow.

A longtime advocate for Parkinson’s patients, my mom has testified before Congress several times about funding for Parkinson’s research. On one of those trips to Washington D.C., she met Michael J. Fox, who was there giving testimony of his own. Just a short time later, he would create his own foundation to advance research, becoming a tremendous advocate and symbol of hope for the PD community.

My dad staying at home made our relationship stronger. He was my hero. Although PD prevented him from playing ball or coaching me at sports, he gave me lessons in life. Perhaps my greatest memory of my father is that he was a gentle giant. Parkinson’s softened his voice and slowed his movements, but he was still Dad – leader of our clan. Possibly the greatest lesson he taught me and my siblings was humility. When I helped feed him, dress him, wipe drool from his chin or assist him up from a chair, he may have sometimes thought of himself as a burden. I never felt that way.

Force of Life

Through all the turmoil of his constantly changing symptoms, Dad kept the best attitude. He often found humor in experiences that could be upsetting. Sometimes when he would fall and I, as a child, couldn’t pick him up, he would just start laughing. His laughter became infectious and there was no way he was getting off that floor anytime soon. He had a loving, devoted wife and six healthy children and “that is all a man — a real man — could wish for in life,” he once said to me emphatically.

As our family has grown to include grandchildren and great-grandchildren, we all carry the passion and hope for new treatments and a cure. We support research, education and, at every opportunity possible, we share our story. We may be a long way from a cure but we can’t give up.

Dad, I hope you are proud!