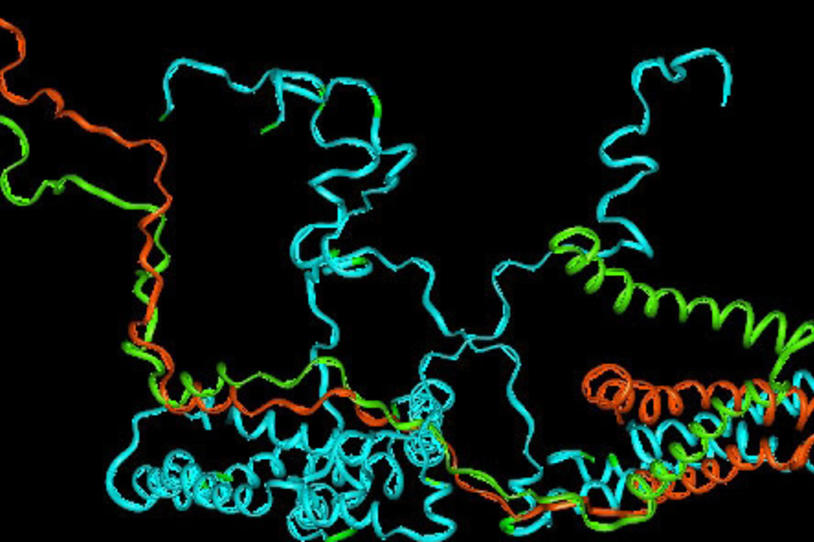

Since its discovery in 1997, it has become increasingly clear that the protein alpha-synuclein is closely associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD). But while it’s known that all people with PD experience a build-up of alpha-synuclein in their brains (called Lewy Bodies), it’s still unknown what, if any, causative role alpha-synuclein might play in the onset and progression of the disease itself.

One problem that researchers have encountered when trying to get to the bottom of this question is that alpha-synuclein exists in different forms in the body, called “species.” And scientists don’t yet know which species are the bad ones that might be causing PD to occur.

The Michael J. Fox Foundation (MJFF), who has devoted more than $55 million to alpha-synuclein-targeted research on the whole, is addressing this problem head on, funding scientists to learn more about which species of alpha-synuclein might be toxic. In fact, MJFF has convened a consortium of research groups to answer this question, which includes one project analyzing post-mortem brains for the existence of particular types of the protein.

In basic terms, the proliferation of different species of alpha-synuclein is based in variant naturally occurring chemical processes that affect the make-up of the protein in the cell. For example: the alpha-synuclein might be “phosphorylated” if it interacts with salts called phosphates, or “glycosylated,” if it attaches to sugars called glycans.

Scientists are intent on knowing which of these chemical interactions might be leading to the onset of PD, as biotechs could potentially develop drugs to stop these processes from occurring. It’s also possible that detecting the presence of a toxic species of alpha-synuclein in a person’s body could provide a biomarker, or an objective measure of diagnosis and disease progression, of PD. Currently, no such Parkinson’s biomarker exists.

Mark Frasier, PhD, vice president of research programs at MJFF, explains:

“The idea is that, if we are able to determine that one form of alpha-synuclein is bad, either in certain levels as compared to controls, or even just its overall presence in the body, we might be able to use it as a biomarker for PD. And down the road, if we were to develop a potential disease-modifying drug for PD, we might be able to measure its therapeutic effect based on how levels of this type of alpha-synuclein in a person’s blood or cerebrospinal fluid change over time.”

Currently, the main species of interest for most researchers in the Parkinson’s field is phosphorylated alpha-synuclein. One group from the University of Washington is being funded by MJFF to determine if this species could be a biomarker for PD. Frasier is hopeful that data gleaned from this particular project could be integrated into the Foundation’s landmark biomarker study PPMI in the future.

There’s still a long ways to go to home in on which of these species might be the one most associated with PD, and what it’s role in the disease might be. The good news is, projects are moving forward: In two months, the budding consortium meets again to share data and ideas.

“For now, developing drugs against any specific kind of alpha-synuclein, or using such a species as a Parkinson’s biomarker, is pie in the sky,” says Frasier. “But I’m optimistic that we’re moving in the right direction, and that we have convened the right kind of group to get closer to finding answers.”